28 Hubin Road, sometimes also known just as “28”, is the flagship restaurant of the Hyatt hotel in Hangzhou, on the banks of the West Lake, the city’s main tourist attraction. It has a reputation well beyond the city, and one Chinese magazine proclaimed it the best restaurant in China. It specialises in the local Zhejiang cuisine, one of the eight traditional cuisines of China (the others being Cantonese, Sichuan, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong and Anhui). One difference in this cuisine, for example, is that the vinegar used is black vinegar from Zhenjiang. The restaurant opened back in January 2005.

The restaurant is located on the ground floor of the hotel, its kitchen now headed by chef Colin Cheng, who has worked here from the opening and worked his way up to executive chef.; he had previously worked in some Shanghai restaurants. The dining room is quite large and there are no less than seven private dining rooms. We ate in one of these this evening, and had a surprise tasting menu prepared by the chef. Assorted tasting menus of varying length were available, one at CNY 500 (£57), another at CNY 694 (£79) and a full a la carte selection.

I had read that the restaurant had a large wine collection, but the list that I was shown was quite short and also omitted vintages; perhaps a more extensive list exists that we did not see. The wine menu shown featured labels such as Dr Loosen “Dr L” Riesling at CNY 350 for a bottle that you can find in the high street for about CNY 95, the very pleasant basic Guigal Cotes du Rhône at CNY 400 compared to its retail price of CNY 115, with a few posher bottles such as Krug NV champagne at CNY 3880 for a bottle whose current market value is CNY 1,494.

To begin the meal an array of cold dishes were served. Slices of poached five spiced pigeon egg jelly were topped with marinated goose liver. This was pretty to look at and had very good flavour, the richness of the goose liver balanced by the spices (16/20). Cubes of lotus root with sticky rice were flavoured with aromatic osmanthus flowers (the city flower of Hangzhou). This was pleasant rather than thrilling, but there is a limit as to how exciting you can make lotus root rice (14/20). A mixed dish of cold chicken, abalone, prawns and beans had pleasant abalone and prawns but lovely chicken, whose flavour was excellent and reminded me of what good chicken used to take like many years ago (15/20 average). Marinated beef shank slices were served with potato noodles and a spicy sesame sauce. This was excellent, the beef tender, the noodles delicate and the sauce lovely, with a distinct spicy kick (16/20). Tossed smoked and dried bamboo shoots with scallion were stacked into a little pile. These were pleasant enough, quite aromatic from the smoking process, but also a touch dry (13/20). Braised sweet and sour pork spare ribs were flavoured with more aromatic, citrus scented osmanthus. These had lovely flavour, carefully cooked and tender, the sweet and sour sauce in precise balance (16/20). Overall, I would assess this course as 15/20.

After this the menu started to unfold with a sequence of hot dishes. Boiled fish soup, called song sao, is a Hangzhou speciality, this version using three different local fish crucian carp, a type of cod, and snakehead. The broth was flavoured with black fungus and spring onion (scallion), with a little bottle of rice vinegar being offered to be poured to each diner’s personal taste. The soup was quite thick, an effect normally achieved by a thickening agent like cornflour. However in this dish there was no such assistance, a clean flavour resulting. To me it was merely very good (16/20), but my Chinese gourmet companions were bowled over by the consistency of the soup and its purity of flavour, so I suspect that a great deal of skill was involved here and that my western palate is underestimating it.

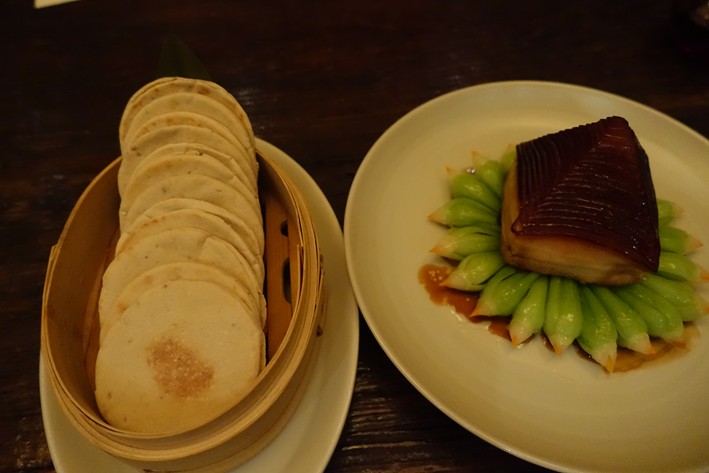

Next was one of the two dishes that the kitchen is especially noted for. Dongpo pork, named after a Song dynasty poet, involves a slab of pork belly that has been through a multi-stage cooking process. The pork belly is braised, simmered twice, sautéed and steamed, the slow cooking process reducing much of the fattiness of the pork belly. It should be of a precise consistency that allows slices to be easily separated from the slab by chopsticks. Here it was shaped into a rectangular slab and presented on a bed of baby bak choi, served with chestnut pancakes. Lurking inside the pork slab was a centre of bamboo shoot hearts, only the most tender parts of the shoots being used. The pancakes are designed to be little pouches, into which you place the thin slices of pork and the bamboo shoots before consuming them together. The texture of the pork belly was remarkable, and although it was rich there was none of the overt fattiness that you usually encounter with pork belly. The cut of the pork is crucial to have a uniform fat to meat ratio, otherwise the pyramid shape won’t be even since the expansion of the fat is different than the meat when cooked. Considerable knife skills are required to make this dish. The chef targets 20 spirals in the meat (twice that of some alternative recipe versions), meaning his cuts have to be ultra thin. The pork is slowly steamed for three hours to get all the grease dripped out from the belly; this ensures the creamy fat structure remains without the pork seeming oily. The bread is made with chestnut powder and flour, so that any excess grease will soak into the bread. Finally, even the bak choi themselves were exceptional, very tender and an ideal foil to the richness of the pork, along with the very tender bamboo shoot hearts. This was an impressive and gorgeous dish that tasted every bit as good as it looked (20/20).

Wok fried Longjing shrimps were next. As often with Chinese dishes, there is a legend about how it came about. A Qing dynasty emperor was seemingly particularly fond of Longjing (Dragon Well) tea, so much so that he would carry some of the leaves with him stuffed into the pockets the robes that we wore. He also supposedly had a habit of disguising himself as a commoner and wandering about amongst his subjects, covering his imperial robes with a cape. I know, I know, but bear with me... One night he was in disguise at an inn and asked a waiter to make him some of his favourite tea, taking some of the leaves from his robe pocket inside his cape. The waiter caught a glance at the imperial robes as he did this, and rushed back to the kitchen to break the news to the kitchen staff. The chef was so shocked that the emperor was in his humble inn that, distracted, he used some of the tea leaves instead of the intended scallions in a prawn dish that he was making. The emperor tried the dish and loved it, and another Chinese recipe legend was born. Well, so goes the story. There must have been an awful lot of eccentric emperors over the years given the number of times they crop up in recipe creation in China. Back to reality, the tiny prawns used here were of a particular type that defy easy English translation but are greatly prized. The prawns, according to tradition, are marinated in egg white, cooking wine and cornstarch, then fried in a wok with an infusion of the longjing tea leaves. They were simply served with a garnish of more tea leaves. The prawns, it has to be said, had terrific flavour and were very carefully cooked, the aromatic tea quite a gentle flavour so enhancing, but not distracting from, the prawns. This was quite a simple dish but was impressively executed, the key being the exceptional quality of the prawns (17/20).

The final savoury dish was the highlight of the meal, and the dish that this restaurant is best known for. By now you will have gathered that behind any famous Chinese dish is a recipe creation legend, and that there is more than a sporting chance that an emperor is involved. Indeed this dish is so famous that there are multiple competing legends. In the version I was first told in China, a beggar stole a chicken from the emperor, who was incensed and sent troops out amongst the populace to find it and punish the miscreant; this emperor was presumably unusually keen on poultry cost control and stock-keeping at his palace. Knowing that soldiers were on the look out for the distinctive aroma of smoke from the fire used to cook the chicken, the beggar, an unusually inventive cove, had the idea of encasing the bird in lotus leaves, encasing it in mud to form a clay shell, and slow-cooking the chicken by burying it in a hole in the ground where he had lit a fire, thus avoiding any tell-tale smoke. He later dug up the cooked bird and got away with his crime. There are several alternative, duller, forms of the story behind the dish, but as this is a restaurant review rather than a recipe history text, you can look these up yourself if you like. The version at 28 still uses a proper clay casing (some variants elsewhere use a pastry casing instead). The inventor of the recipe, former executive chef Peter Zhou (since promoted with the Hyatt group and now general manager of Park Hyatt Ningbo) tested two hundred different recipes for Beggar’s Chicken before settling on this one.He tried varying the type of soy sauce, type of ginger and the cooking methods, even the number of lotus leaves used in the wrapping and the thickness of the clay. The current executive chef Colin Cheng further refined this original recipe. Instead of marinating the chicken first before baking at 180C, they now prepare the marinade and bake it together with the chicken at 120C for three hours. The result is meat that is even more soft and juicy. The particular breed of chicken employed here is much prized local one with a name that appears to defy translation into English, and is different from the yellow hair chicken used at Made in China in Beijing in the same dish. It is stuffed with pork belly, scallion and dried shiitake mushrooms, coated with a marinade paste of spices including five spice and soy, then wrapped in lotus leaves before its clay casing is coated around it. The clay case is then cooked for three hours. When the egg-shaped case is served, it is smashed open with a hammer, which as a guest tonight I had the honour of doing, and much fun it was too; you need to be reasonably forceful to break the clay casing open. The lotus leaf parcel is then unwrapped and the bird emerges from its nest, and is then basted with chicken jus prior to serving. The characteristic of the dish is that the slow cooking process means that the tender meat easily slides off the bone, the pork belly stuffing helping to avoid any dryness. The flavour of the chicken was terrific and it did indeed have remarkable, silky texture. The cooking juices themselves were as much of a treat as the meat, having been flavoured by the marinade and having great intensity. I raved about the quality of the chicken juices so much that a bowl of rice was brought so that I could pour the last of the cooking juices over the rice rather than waste the last of the precious liquid. This really was a gorgeous creation, and fully justified its reputation (20/20).

Around this time some supplementary dishes appeared so that we could briefly sample some other creations of the kitchen. There was some particularly good xiao long bao with a filling of stuffed hairy crab roe, featuring an impressive number of folds in the dumplings, something requiring considerable skill. There was a dish of tossed noodles with sea urchin and vegetable julienne, and wok fried cabbage with crab roe, but by this time we were both quite full and very short of time to make our long journey home, so it is unfair to comment on these extras. To finish, an impressive collection of desserts appeared, but by this time we were running perilously late to get the train back to Shanghai, so only had time to briefly taste these as we packed up and headed off. Hopefully on another occasion I will get the chance to give proper attention to the creations of the pastry chef.

Service was very good indeed, though we were doubtless seeing the very best of it. We were dining in a group including a published Chinese food writer and seemingly gourmet celebrity, who modestly denies this status despite the warm and deferent greetings from the management of the hotel on his appearance suggesting otherwise. Other than the staff carrying him in on a palanquin it could have been hard to think what more they could have done to make us welcome. Our group was even treated to a formal tea ceremony (this being the area where the famous Dragon Well tea is grown) when we arrived by a lady who I assume was the tea sommelier. When it came to catch our late train back to Shanghai we were entirely unable to get a bill, the restaurant manager insisting that the meal was his personal treat. With the clock ticking away we finally gave up arguing, left a large tip in cash for the staff and made a dash for the train, which we barely made, but that is another story.

If you ate from the a la carte or from the cheaper tasting menu and shared a bottle of modest wine then a typical cost per person might come to around £85. Although my food author friend’s presence meant that we definitely got well looked after, there was no doubting the quality of the dishes here. The two signature dishes of the kitchen, the dongpo pork and Beggar’s Chicken, were outstanding by any standard. This is clearly a very fine restaurant with the ability to produce some remarkable dishes.

Add a comment

Thank you for submitting your comment, this will be checked and added to the website very soon.

User comments